Are Amphibious houses the answer to flood prone areas?

Followers of the television program ‘Grand Designs’ will be familiar with houses that can float. An episode in 2014 followed a couple whose dream was to build the UK’s first amphibious house on a small island in the River Thames. After many setbacks, including floods during construction, the house was completed in late 2014, a striking, moated structure clad in ‘dragons’ scales’ with wide, watery vistas.

Houses that float may sound like the stuff of science fiction but they represent an innovative solution to flooding. Is it time to float this new approach on a national scale?

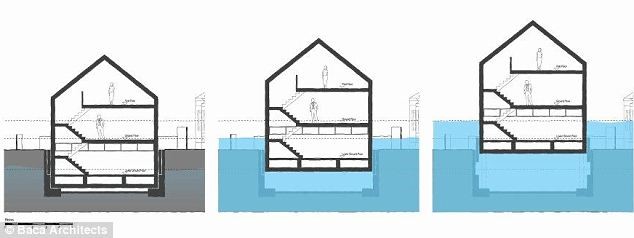

The house on the River Thames replaced an old bungalow that had been plagued by floods. The new house is built into a concrete dock secured deep in the ground. As the water rises, the dock gradually fills, gently lifting the house off the ground. “Dolphins” (fixed vertical guideposts) keep the house from floating away if water levels get too high. The garden’s multi-level terrace design gives the homeowners plenty of warning of rising waters. The lowest level is planted with reeds and other marsh plants and will fill with water first. Next comes a level with flowers and shrubs, and the top two terraces are lawn and a patio. The house is designed to rise to 2.7 metres – much higher than would be needed to protect from even the severest of floods.

Recent examples of the devastation caused when traditional flood defences have failed include New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and the destruction across south-east Asia in the wake of the 2004 tsunami. There have been calls to change the way we think about water, seeing it as something to live with, rather than to battle against.

This is certainly the view of Robert Barker, director at Baca architects, the company that designed the house on the River Thames. He told the Guardian, “We’re looking at a shift in thinking towards the idea of non-defensive flood risk (…) how flood risk can actually generate better architecture and better planning. So we see water as an asset. Instead of seeing it as a foe, we see it as a friend”

Another interview with Robert Barker of Baca Architects.

Although this type of house is new in Britain, the technology has already been embraced in other countries around the world. Holland is a country at risk of extreme floods. More than a quarter of the country lies below sea level. Many Dutch towns are threatened not only by the sea, but also by the River Rhine. For a time, all building in flood zones was banned. But pressure of population led the government to relax restrictions – but only if new buildings were amphibious. Now whole communities exist in formerly uninhabitable places.

Maasbommel is one. Beside the recreational lake of Goulden Ham, the community includes 46 semi-detached houses. The majority are amphibious (some can rise five metres), and a few are permanently floating. This development has won a number of architectural awards and has drawn interest from around the world.

As long ago as 2005, Dick van Gooswilligen of construction firm Dura Vemeer was enthusing: “Housing of this type is the future for the delta regions of the world, the ones which face the greatest danger.”

© Dura Vermeer

So, almost ten years on, what is holding up the widespread construction of amphibious housing?

The amphibious houses in the Netherlands, and the one built in the UK, have been more expensive than conventional housing – by around 20% to 25%. However, this is to be expected for such a young innovation. As expertise grows, cost savings will become apparent. For example, land prices are often much lower in areas likely to flood.

There are certainly challenges. Utilities have to be connected to the property using flexible piping. Baca Architects have not revealed how exactly how they achieved this in the Thames. Buyers and insurance companies will also need some convincing that these new homes are safe and functional.

With the government pledging to build a million new homes by 2020, this new approach to building could open up the possibility of developing previously untouchable land. It could also provide thousands of homeowners with the peace of mind that they can live with the elements, rather than constantly battling against them.